A Path to Opening Up Twitter

Key Takeaways

- Centralized proprietary recommendation algorithms are hard to get right. Social media platforms are failing us as sole arbiters of truth on their platforms.

- Let’s open up the ability for 3rd party developers to create recommendation algorithms on Twitter services.

- Instead of jumping straight into a fully decentralized protocol, which is risky and takes a lot of work, let’s test the underlying assumptions on production Twitter first.

- If decentralization is the ultimate goal, any work we do here will be useful on the path.

Earlier this month, Jack Dorsey issued a tweetstorm, declaring the formation of a new team to explore an “open and decentralized standard for social media”. The response from the community has been incredible, with tens of thousands of retweets and likes in just a couple of weeks. I’d like to suggest a potential iterative path forward. I have seen too many good projects under smart leadership slowly fade because they were building something so radically different all at once that no one ultimately wanted. I worry that an “independent” team of 5 open source developers designing a completely new architecture may suffer the same fate if Twitter finds it too costly to switch later on. An iterative path tightly looped with Twitter’s production would allow the effort to both, experiment with smaller scoped experiments in the market quickly, as well as test whether the architecture is compatible with Twitter. A sequence of upgrades that is compatible with Twitter’s technical architecture is far more likely to succeed in the end. One that is compatible, or even better, reinforces Twitter’s business model will accelerate our path towards decentralization.

As someone that has been doing research and building software in the decentralization space for over a decade, this feels like a significant step forward by a top executive at a social media company. For the first time in my recollection, one of the biggest tech companies has signaled the willingness to open up their core platform in order to work with the public community on solving some of the biggest problems facing our society today. I’m incredibly excited to see this opportunity and I hope we all make the most of it.

The Problem

Before we prescribe a particular solution, like blockchain or a standardized federation protocol or decentralized storage, let’s first explicitly define the problem that we’re actually trying to solve. Jack lays out 3 in his post:

1. Centralized enforcement of global policy

“First, we’re facing entirely new challenges centralized solutions are struggling to meet. For instance, centralized enforcement of global policy to address abuse and misleading information is unlikely to scale over the long-term without placing far too much burden on people.”

Imagine all the world goes to your computer for their tweets and you were solely responsible for figuring out what people see in their feed, often influencing a user’s sense of truth. That is the challenge major social media companies are faced with and it is a difficult job. Wolfram attributes the root issue to “ethical incompleteness”: “There’s no finite set of principles that can completely define any reasonable, practical system of ethics.” A centralized arbiter of truth doesn't work on a global scale across large populations because what is considered ethical and right to one group may not be to another, putting social media companies in a lose-lose situation. Take down one thing to placate one group, alienate another.

2. Proprietary recommendation algorithms

“Second, the value of social media is shifting away from content hosting and removal, and towards recommendation algorithms directing one’s attention. Unfortunately, these algorithms are typically proprietary, and one can’t choose or build alternatives. Yet.”

The user experience of a social media platform is largely driven by its recommendation algorithm, which analyzes user behavior to recommend things that may shape a certain information narrative. However, these algorithms and models are typically proprietary, so it is difficult for the public to assess what agenda the algorithms advance. As in the case of election interference, the algorithms may even be gamed by outside parties. Centralized proprietary systems make it difficult for outside researchers to study existing algorithms and suggest alternatives.

3. Steering towards outrage

“Third, existing social media incentives frequently lead to attention being focused on content and conversation that sparks controversy and outrage, rather than conversation which informs and promotes health.”

Twitter’s own letter to its shareholders highlights the issue. Their key performance metric involves “monetizable daily active users”, or the number of users on any given day who can be shown ads. Thus, the platform will be incentivized to steer users towards content that will keep them engaged on a daily basis, which in practice results in conversations that spark outrage. This may de-emphasize other values such as, “Is the user well-informed?” or “Are we having healthy conversations”? One way to keep the social media platform neutral is to separate out the influence over surfaced content from the content itself.

An Actionable Step Towards Decentralization: A Marketplace for Recommendation Algorithms

If relying on a sole centralized arbiter of information is a poor and unscalable choice, then naturally the only alternative is to open up the platform to allow others to innovate on recommendation algorithms. Rather than jump straight into a decentralized protocol, let’s first take a small step that allows us to test some of our assumptions about these problems on the market.

Each unique combination of recommendation algorithm and user interface, which we’ll call a lens, provides a completely different experience to the user, even if the underlying data is the same. For example, one lens could be optimized for providing the most accurate and relevant information in the case of an emergency, such as a mass shooting, alerting nearby users to potential danger. Existing practices around hashtags require the users posting to coordinate, which may not always happen.

By opening up Twitter to support external lens publishers, Twitter will enable anyone to build a robotic editor, who can generate real-time feeds for every Twitter user. There exists an infinite universe of lenses, each optimizing for different goals and perspectives, which allows different communities to experiment towards what works best for them and enables diversity of opinion. The abstraction of a lens opens up the ability to publicly experiment and debate how we, as a society, want algorithms steering our attention. Any decentralized protocol will need to solve this problem as well, and testing our assumptions on production Twitter will lead to less costly and quicker lessons.

Note: This idea has also been proposed in other articles, including by Wolfram and Masnick

Prior Art in Decentralized Social Media

With the rapid rise of popularity of social networks like Facebook in 2004 and Twitter in 2006, researchers were concerned that the future of the social web would stay closed and proprietary, like its walled-garden incumbents. In 2007, a group of prominent internet entrepreneurs penned the Bill of Rights for Users of the Social Web, listing data ownership, control, and freedom as fundamental rights of users. This motivated the start of an era of social network software striving to achieve decentralization. There were two main flavors of decentralized social networks: federation and peer to peer.

Decentralizing social media through federation

The main philosophy behind decentralization through federation is to enable data portability, interoperability, and communication between different network providers through agreed-upon protocols. Imagine if you could connect all your content between Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr with one account, interact with users of any of those platforms, and leave any one of them arbitrarily.

StatusNet was one of the earliest attempts at this in 2008. Then, in 2012, a W3C community group was started to develop the OStatus standard, which was a suite of protocols to support different social networking primitives such as Atom and ActivityStreams for syndication, PubSubHubBub for publishing notifications, Salmon for reply notifications, and Webfinger for discovery and identity. ActivityPub was later introduced in 2018 as the successor to OStatus as a remedy to its accumulated complexity.

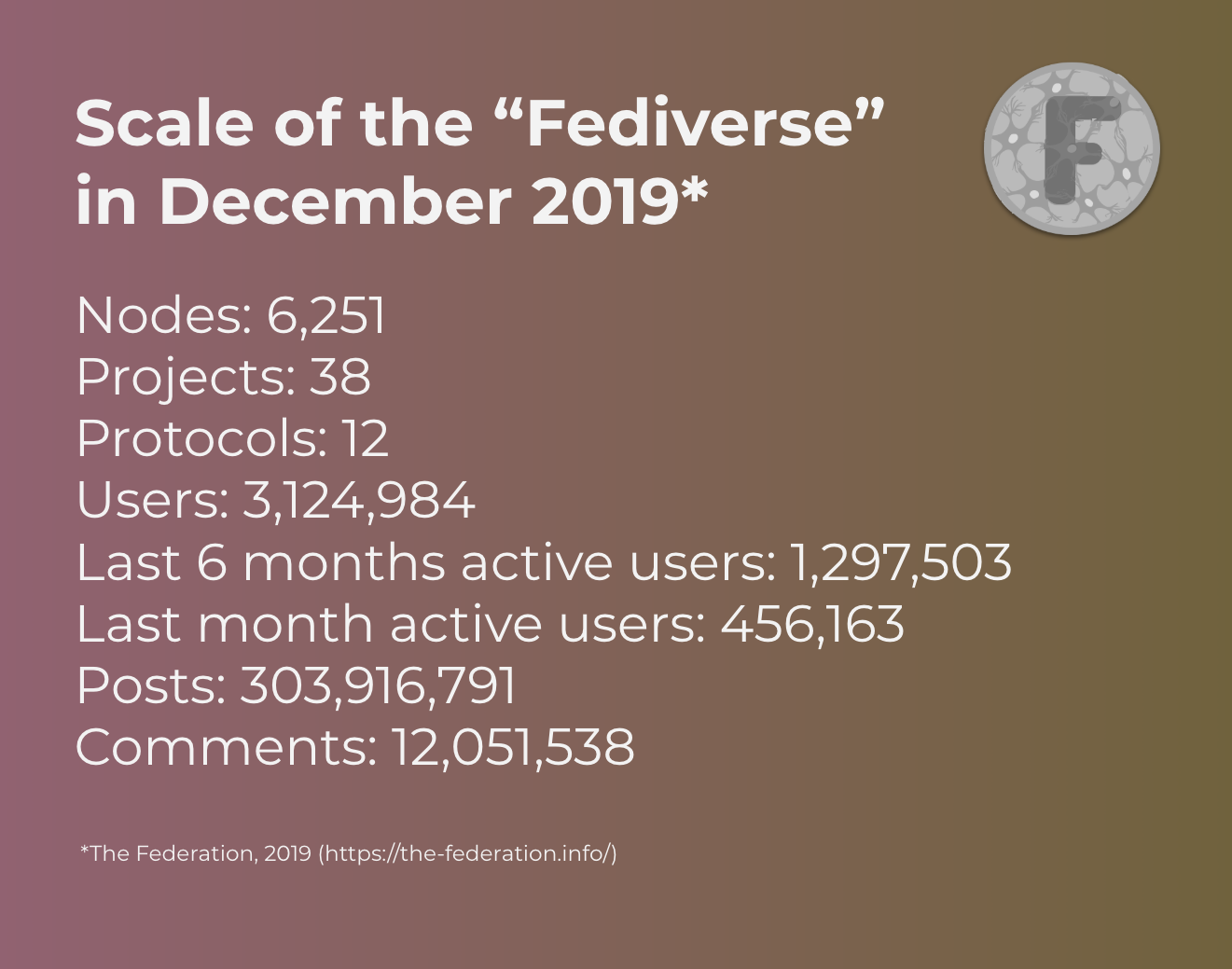

With the advent of protocols to make the social web open, federated social networks such as GnuSocial, Diaspora, and Friendica were started in 2010 aimed to be the open alternative to beat Facebook and Twitter, with Mastodon (2016) being one of the more recent iterations. Here is an estimate of the current numbers of the “Fediverse”:

Almost a decade in, adoption of the “Fediverse” has not taken off. Why?

1. Interoperability between federated services is poorly implemented.

According to this research, interoperability between federated services is “flawed and error prone”, especially since each system’s API endpoints have sparse documentation. This results in a failure of bootstrapping adoption via network effect.

2. No interoperability with incumbents.

These systems are not interoperable with closed and proprietary incumbents like Twitter and Facebook, who may not have a financial incentive to implement any of these open standards and risk losing users. Even companies that have a history of deploying federated protocols may move away from it if there is insufficient usage of federation features or slows down product innovation.

3. Lack of capital and resources to iterate.

These open social networks don’t have recurring ad revenue remotely near the order of magnitude of their titan counterparts, and thus can’t compete with their armies of software engineers and product managers employed to improve user experience every single day.

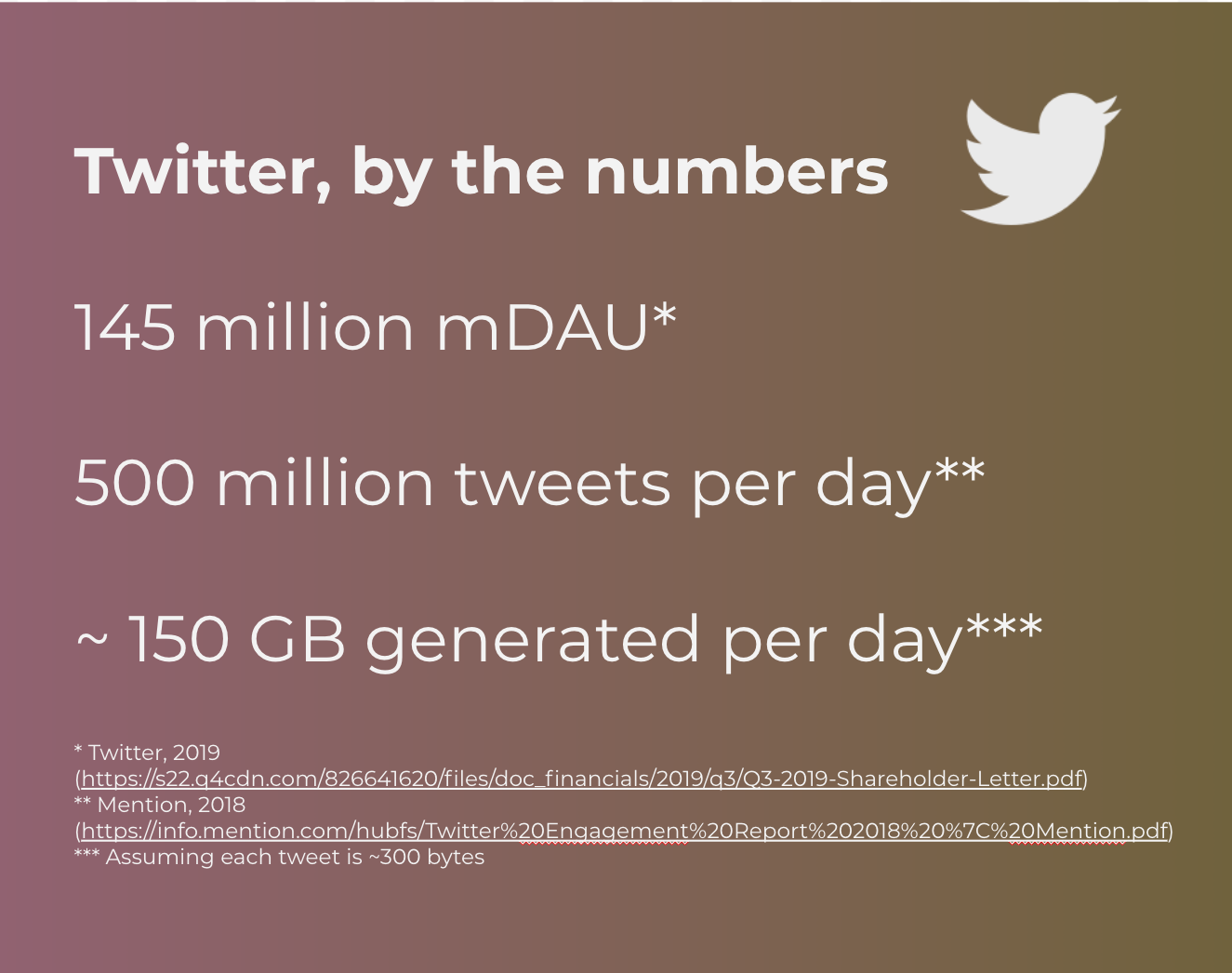

Even if adoption was high, the “Fediverse” has not yet been battle tested to handle Twitter scale. Take a #hashtag search for example. Searching #blessed over heterogeneous federated systems would require you either to 1. spam every single server with a #blessed query and join all the results in a third party system or 2. flood every single server with all tweets for the query. With Twitter’s generating ~150 GB of tweets every single day, handling this scale of data simply would not be viable with the infrastructure and resources of these federated systems.

Federated systems do provide a physical separation of services, which can be used to implement the lens abstraction. For example, different servers could tailor their recommendation algorithms towards different communities. However, each server is also responsible for maintaining fault-tolerant service; if your local service goes down you may lose access. In our proposal, we suggest to enable this abstraction while still outsourcing service reliability to Twitter’s existing scalable infrastructure.

Decentralizing social media through peer-to-peer applications

Peer-to-peer applications (P2P) provide another alternative. In P2P systems, the content is distributed across a peer-to-peer network rather than relying on any central point of failure. P2P systems are designed to tolerate a certain number of failures, typically by automatically routing to one of many data replicas. Lookup metadata is stored in a routing table, such as a distributed hash table (DHT), which tells users which machines store the data they’re looking for. Popular content is usually replicated on more nodes to share the load, and will be faster to access on average. However, P2P-based systems are generally slow for querying data. For example, most DHT systems require a recursive search that is logarithmic in complexity (requires log(n) hops). PeerSoN, Safebook, Cuckoo, and Megaphone have all been attempts at a P2P social network solution. P2P systems often suffer from longer latencies, affecting the user experience. Early P2P systems relied on volunteers to participate in the system, without strong incentives to stay reliably in the system. Furthermore, many early P2P systems were designed relying on semi-honest parties, and become vulnerable to severe security threats in the face of malicious parties.

Recent systems, including many in the blockchain community, started exploring P2P designs under stronger threat models, such as BFT or BAR, where some fraction of the network can be actively malicious. Blockchain-based systems have innovated on using resource scarcity, such as hashing power in proof-of-work or cryptocurrency in proof-of-stake, to address security issues like Sybil attacks, and on using economic incentives to incentivize good behavior. Blockchains typically entail a relatively expensive consensus protocol in order to fully replicate a consistent view of data across a number of participants, known as miners in Bitcoin. Steemit stores all content data directly into the blockchain, the data is always accessible after confirmation. But there are challenges associated with pure blockchain solutions. Consensus protocols, especially over a wide-area network can be expensive and bottlenecked by replicating data over the network. For example, we recently measured that a simple token transfer on Ethereum was 5 orders of magnitude more expensive than performing the same operation in a cloud server. Even Steemit encourages developers that wish to query the on-chain data to use their “consensus interpretation” layer written in Python, which enables generating a replica of all chain state cleaned and organized into a SQL database with indices. This type of solution could be quite expensive for social media data at Twitter Scale.

Because pure blockchain solutions like Steemit face many challenges with storage and querying, other blockchain projects try to use a hybrid solution by offloading data off-chain to a DHT-based system like IPFS. Voice and Akasha are attempts at accomplishing this. Not much is publicly known about the production performance capabilities of these projects, Voice is built on the EOS blockchain, while using IPFS for data storage. While it is likely to face the same challenges as other DHT-based systems, it remains to be seen if these systems will offer a comparable user experience at Twitter scale.

Goals

Where previous projects have faced a lack of adoption due to many of the challenges stated above, in order to realistically bring a solution to the Twitter masses, we must properly address at least these three primary goals:

- Scalable performance: Any proposed system must provide a path to supporting at least as many users as Twitter has today. The changes should also not negatively affect user experience (e.g. via worse latency), which has been shown to directly negatively affect engagement and ultimately revenues.

- Compatibility with existing business models: Twitter currently earns billions in revenue each year, employing thousands of people in dozens of offices across the world. Any solution that Twitter deploys will likely need to supplement or reinforce this, rather than replace it.

- Incentives to cooperate: Proposing a system where parties outside of Twitter cooperate with Twitter to build a better service is a logistical challenge. Any architecture needs to sufficiently address the incentives that would get outsiders to spend valuable time, effort and resources on it. This is perhaps the best reason to start incrementally --- we need to test in the market whether any particular incentive actually works.

A First Draft Design

In this section, we start by proposing an initial centralized technical design that can be used to quickly test some ideas on the market. Later sections will show how we can expand on this foundation to build a decentralized system.

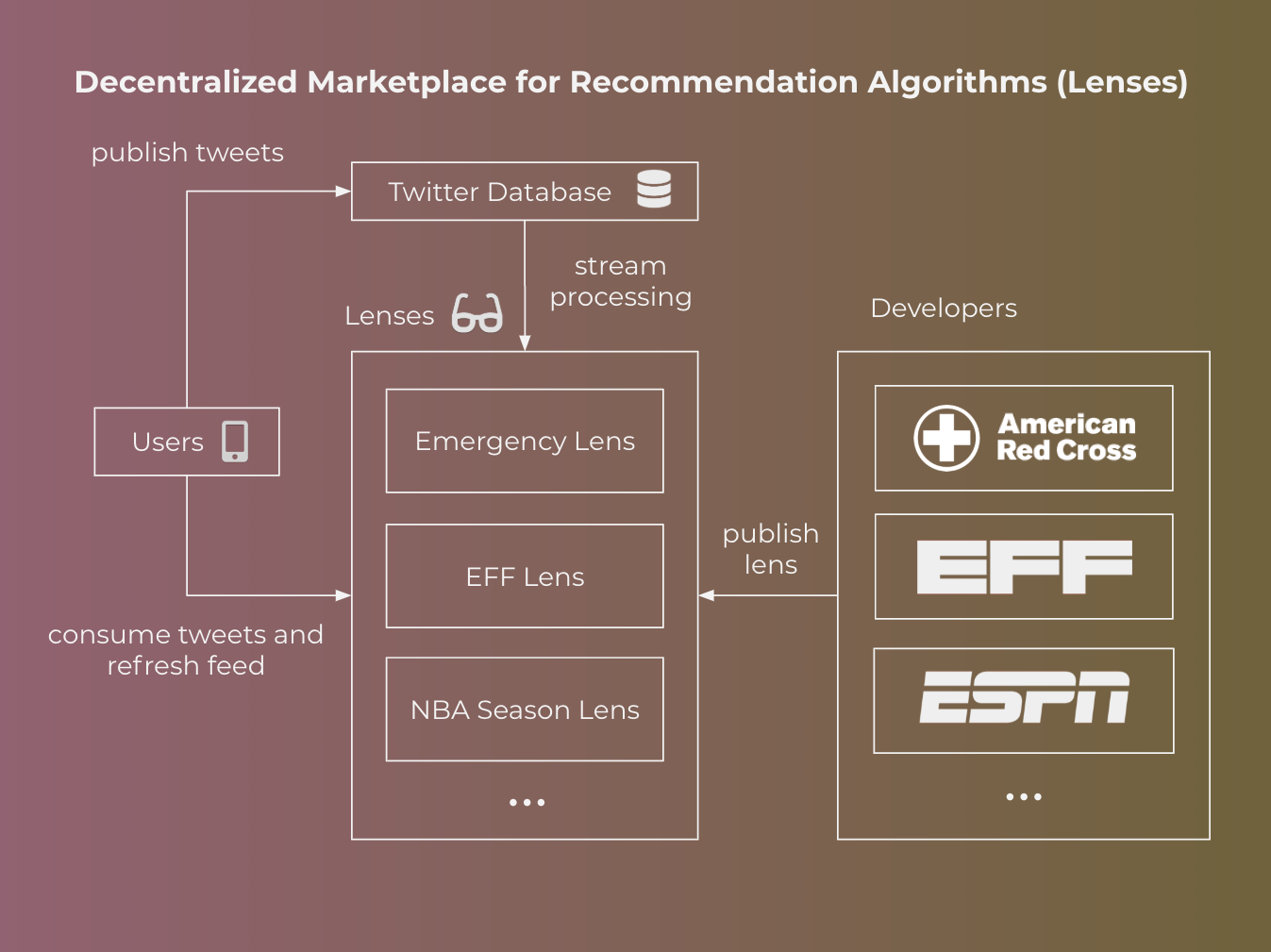

Let’s consider 2 different types of users. Consumers engage with Twitter through official channels --- i.e. web and mobile apps. 3rd-party developers experiment with novel recommendation algorithms for newsfeeds and potentially even new user interfaces to consume Twitter. The platform runs the infrastructure, in this case Twitter.

User experience

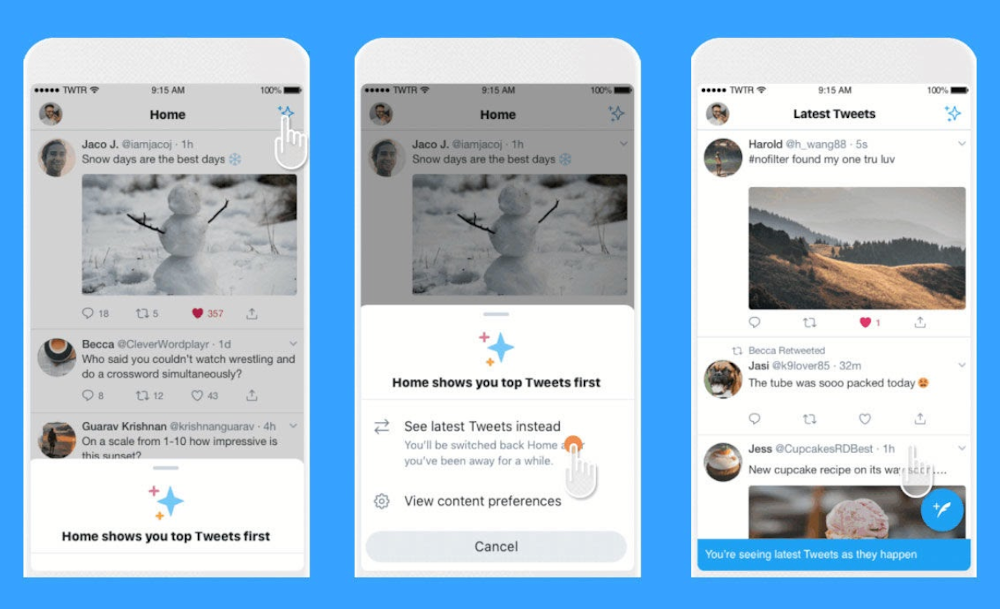

Users continue to interact with the Twitter app the way they normally do. Twitter already exposes a toggle, which allows you to choose between “Latest Tweets”, which shows tweets in chronological order, and “Top Tweets”, a proprietary recommendation algorithm. We propose to augment this interface with new choices, where users can select from a range of different “lenses” from different 3rd-party developers. The native experience does not change, beyond a different prioritization of how content shows up in the app.

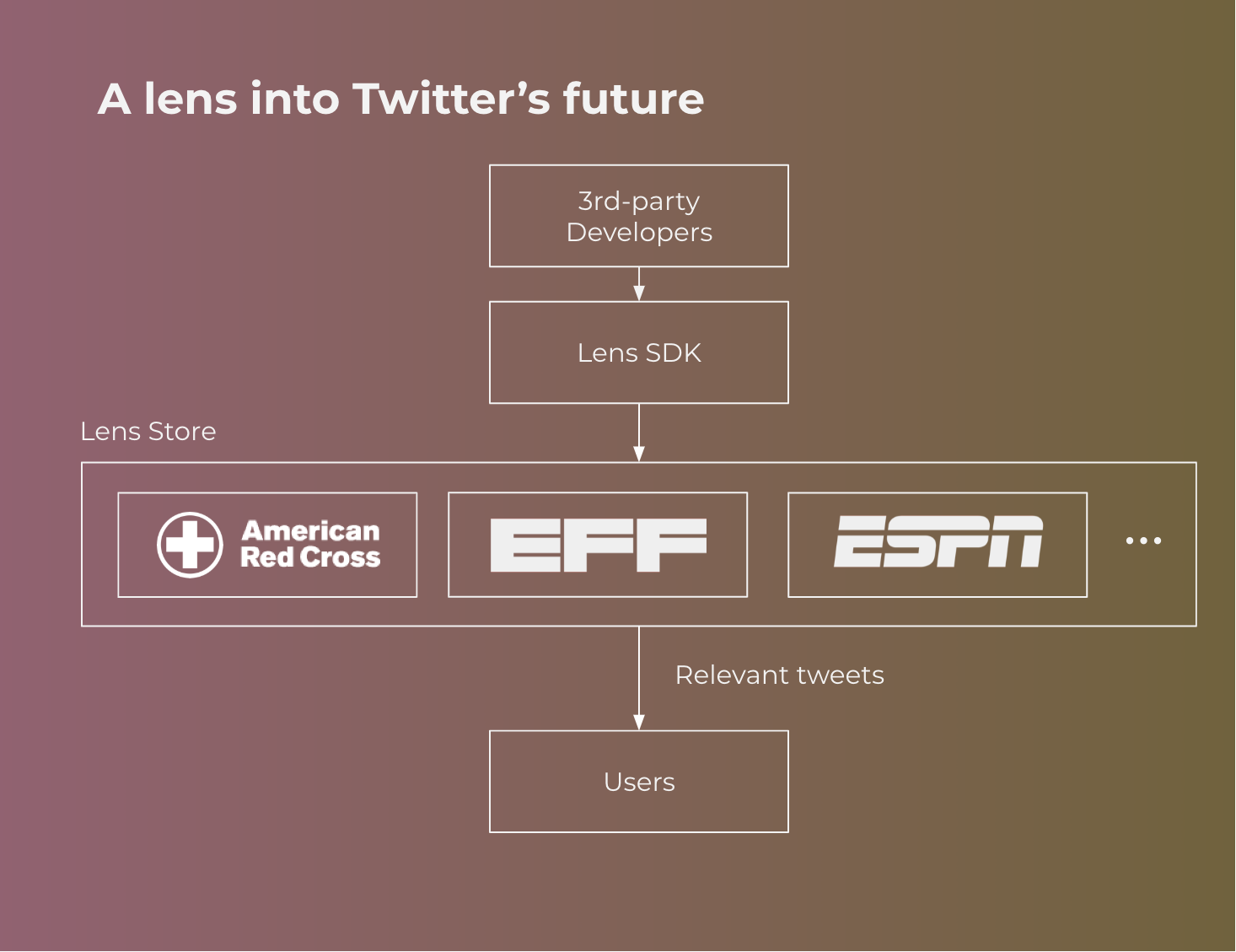

Lens SDK

3rd-party developers use the Lens SDK to create new models and algorithms for content prioritization. This SDK should minimally include anonymous training data and a suite of machine learning and data science tools for generating new models. Unlike other failed attempts to anonymize private data, much of Twitter's high-signal data is already intentionally public. The platform should also expose tools and APIs for monitoring the performance of a deployed lens, including but not limited to metrics around engagement, retention, NPS, and time spent.

Lens Store and Endorsements

Similar to app stores, Twitter can expose new lenses in a hosted store, allowing 3rd-party developers to publish and market their lenses. The store facilitates discovery, search, and reviews. In addition to these standard features, the unique political sensitivity of recommendation algorithms might suggest the need for endorsements. The store could provide a mechanism for outside auditors, such as the ACLU or EFF to audit the code and certifying certain lenses. We leave it as an open question what types of characteristics of lenses might be desirable to certify.

Life cycle of a tweet

Lenses strictly affect the view that users are presented when reading tweets. Posting tweets works the same as the current app. Once a tweet has been posted, Twitter already has sophisticated real-time stream processing infrastructure to compute search indices, calculate statistics (e.g. counts), and run machine learning algorithms. The platform would need to add a sandboxed runtime environment that allows 3rd-party developers to plug in and run their models in this streaming pipeline. This adds complexity in loading and routing to additional sandboxed models. However, we expect these marginal costs to be relatively low compared to a decentralized technical architecture (as we elaborate below).

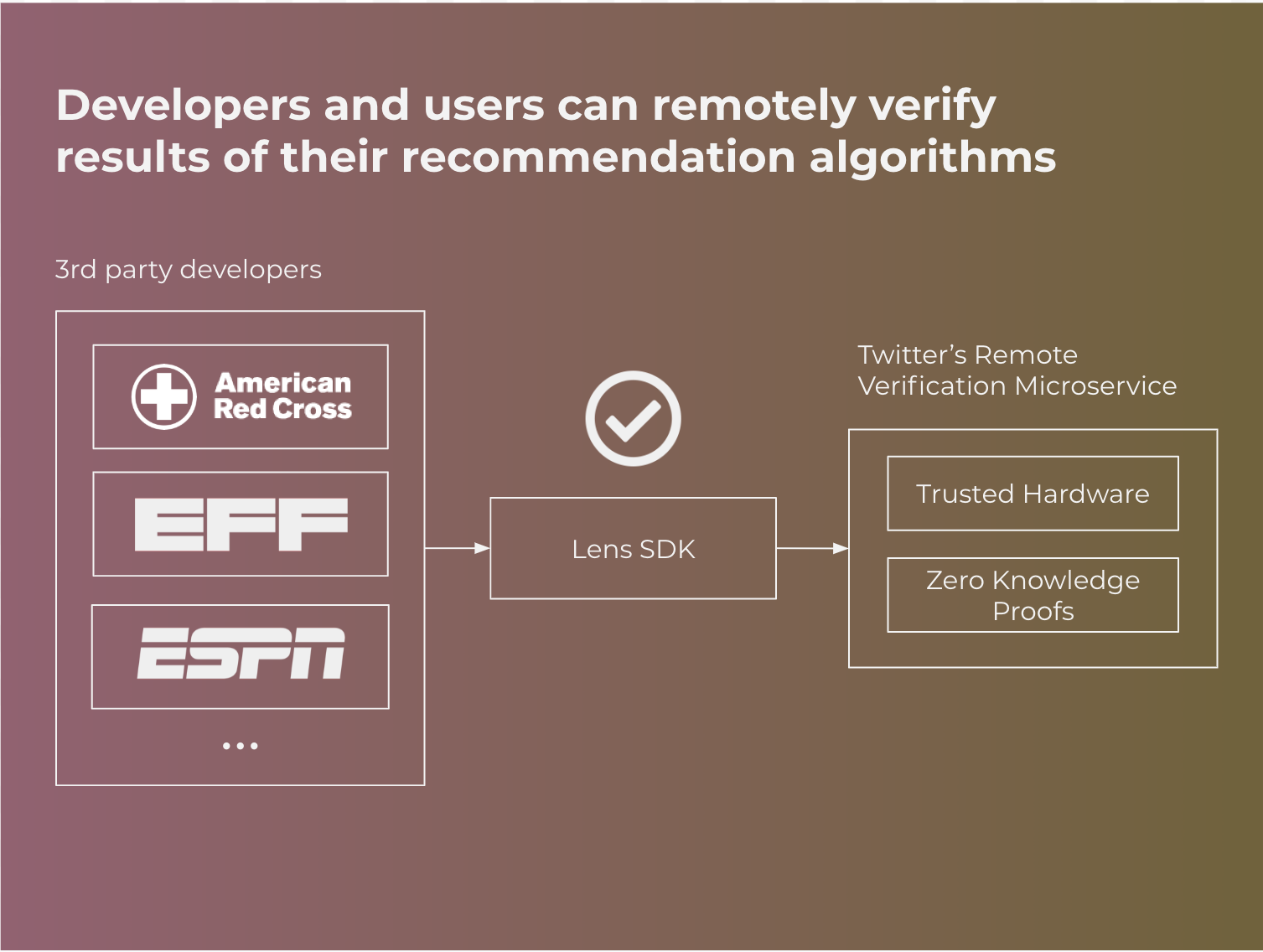

Remote Verification

Informally, verifiable computing is a set of techniques that enable clients to verify that a remote computation was executed correctly on a server. When clients issue a request to the server, the remote server would return a proof along with the result. Crucially, the proof of correctness can be efficiently verified with low computational effort and works even if the server is potentially dishonest. For example when applied to Twitter, any user would be able to request tweets from Twitter and verify a proof that the tweets were the result of a specific recommendation algorithm they chose.

In a world where Twitter is a globally trusted platform, this component may not strictly be necessary. Users would just need to trust that the platform is in fact executing the algorithm they asked for. However, there are a number of reasons to at least begin to design the Lens SDK with this in mind:

- Users and governments are skeptical: Big tech is going through a public reckoning, as more of the public is realizing the power of the systems these companies control. It is really powerful for platforms to be able to claim the system provably behaves correctly even if the platform was not trustworthy.

- Decentralized systems are typically designed for a stronger threat model: Modern decentralized systems, like blockchains, are typically designed for this threat model, where some fraction of the infrastructure can be actively malicious. In today’s security setting, it is difficult to rely on assumptions that everyone on the Internet will behave honestly.

- Interfaces are hard to change: The biggest interface surface we are introducing is at the Lens SDK. Verifiable computing techniques typically require a specialized toolchain. The sooner we can at least get developers building lenses in this way, the more work we can reuse as we continue towards a path of decentralization.

Background Technology: Verifiable Computing

Verifiable computing as a concept was formalized in a 2009 paper and there exists many different mechanisms for achieving its properties. These mechanisms come with various trade-offs in performance, threat model, and types of applications easily supported. Verifiable computing is a rich research topic with decades of papers; below, I’ll briefly summarize trusted hardware and zero knowledge proofs.

Trusted Hardware

Trusted hardware is a large umbrella term for a set of hardware techniques to provide stronger assurances about how a computer behaves. Typically, the hardware includes cryptographic keys that are stored on a secure chip. Assuming the keys only exist in the chip, the computer can then securely encrypt and sign data. For example, remote attestation is a process by which the hardware signs a hash of the hardware and software configuration, to attest to the fact that a particular software version is running. If the keys were exposed the attacker would be able to forge these attestations and steal private data.

This functionality is nearly ubiquitous on most computers via TPM, though other forms also exist such as Intel SGX and Samsung Knox. For a survey of mechanisms, see here.

TPM chips have gained a negative reputation as a tool to help cloud companies enforce DRM on users’ machines, ensuring only authorized software can play copyrighted materials. However, TPM can also be applied in the other direction: allowing clients to verify that servers are running certain software. Researchers have proposed using remote attestation to verify a computer’s bootstrap process, provide cloud services and interoperate with the Web.

Trusted hardware techniques rely on a core assumption that the hardware is capable of generating and storing cryptographic keys securely. However, this assumption has been broken numerous times, most recently in timing side channels, reading clear-text keys off a bus, and ion beam attacks. Not to mention the real risk of a compromised hardware supply chain. However, if we can accept the risks and this cat-and-mouse game, trusted hardware allows developers to run nearly any program with nearly zero performance penalties compared to bare metal.

Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKP)

There is a fast-evolving space of cryptographic innovation in the space of zero knowledge proofs, including ZK-SNARKs, ZK-STARKs, and Bulletproofs. These powerful cryptographic techniques enable verifiable computation with the property of zero knowledge --- the verifier does not learn anything about the inputs to the computation. While not strictly necessary in Twitter’s case because Twitter’s data is by definition public, these systems could be valuable in building something similar for Facebook, where models are trained over semi-private user data.

Cryptographic techniques such as ZKP provide a valuable alternative to trusted hardware, as they do not require any hardware assumptions and their cryptographic assumptions offers protection against a stronger threat model. However, they come with the trade-off of worse practicality. It is orders of magnitude more expensive to generate a proof, than perform the original computation, and often computations need to be expressed in circuits. While researchers have been working on easy-to-use compilers for languages like C, these toolchains are typically more complicated and limited than what developers are used to.

Because I won’t be able to summarize how these systems work in a short period of time, I’ll just point to this excellent primer and list of resources.

Note: This summary does not do justice the decades of incredible research in this space, including interactive proof systems, CS proofs, quadratic arithmetic programs, probabilistically checkable proofs (PCP), server auditing, and many more. I highly recommend working backwards from the related work sections of papers listed to learn more.

This design facilitates and encourages collaboration with the public

Exposing the ability for 3rd parties to deploy their own recommendation algorithms to Twitter and remotely verify it is being run correctly is an incredibly powerful primitive. The power to shape public discourse and steer what users see is too important to leave to centralized proprietary algorithms. This proposal enables anyone to experiment with new recommendation algorithms without putting blind trust in the platform. Potentially, this takes the form of a government-organized effort. Potentially, non-profit efforts like the EFF or academic researchers will come up with a better solution, while other for-profit companies will come up with better ways to tailor to certain market segments with a revenue-sharing agreement. While it is easy to criticize social media platforms, as a society we just don’t yet know what is the best way to shape public discourse on these platforms. One of the most exciting possibilities is the ability to conduct this data science in the open. Anyone would be able to fork an open source lens and publish an improvement with repeatable experiments and results.

Twitter can and probably should continue to publish its own lens over tweets, but it will be one of many that users can select from. On the backend, this is a relatively small addition to their technical infrastructure, and can be deployed much faster than designing and deploying an entire decentralized system. Furthermore by starting with Twitter’s own official client, they can continue to serve ads to users of any lens.

Risks and Challenges

Even with such a limited scoped project, there are a number of risks to this proposal. Here are a few high level ones:

Developer Traction: First and foremost, does the world even want this? Will outside parties choose to spend the effort to build lenses? What are the most effective incentives to drive external participation? It is entirely possible that collaboration at this interface is the wrong one and solving this problem requires a more human touch.

User experience: Is the proposed user interface the right way to expose this choice to users? How often will users even switch between lenses? Will the difference in experience even be noticeable? Rather than switch between lens tabs, would it be more effective to combine multiple machine learning models from different lenses into a single feed for the user?

Market response: Will an EFF-Twitter lens get users and how many will opt to use it? Does this sufficiently address Twitter’s public criticisms? Will this increase the total market share for Twitter, like subreddits have been effective for Reddit? Or will it lead to a more diluted experience with less engagement? How will this impact Twitter revenues? It is impossible to armchair predict how this will resolve. Even though there was public backlash over moving away from a chronological feed, the fact that “Top Tweets” is still the default Twitter user experience implies that they likely see greater engagement with this recommendation algorithm.

Lens Safety: What if there was a lens advertised for cute cat photos, but it actually steered children towards criminal abusers? How would Twitter audit the safety of lenses and remove dangerous ones from its store? While there is a growing body of literature that measures biases in AI models, this is a challenging emerging area. An open platform could both help researchers trying to understand bias in models, but also open up the platform to dangerous actors.

Taking an agile approach to designing interfaces is valuable, it allows us to test whether people even want to interface at this level of abstraction in the first place. Taking a waterfall approach to interface design suffers from similar downfalls to waterfall development in software.

Limitations of this proposal

The proposal laid out above is purposefully limited to focus the market experiments on a narrow problem. However, there are a number of limitations that may draw concern of this proposal.

Content removal and account takedowns

Because the proposal still leverages Twitter’s database infrastructure, they are still subject to the laws and regulations of their datacenter localities. One of the biggest criticisms of social media companies is the policies around “deplatforming”, where controversial speakers are censored from the platform. It is likely that Twitter doesn’t go through all of its tape backups and actually scrubs the bits of deplatformed users, and enforcement is conducted through the application servers. In this case, lenses could include their own policies for how users are banned from the system. For example, one lens could outsource this decision making to a voting committee. However, it is still technically feasible for Twitter to also impose their own content deletion at the database layer. To address this particular threat, the next section discusses a future extension for decentralized databases.

While we can remotely verify the correct execution of a lens, Twitter can also choose to censor particular lenses, leading to the meta problem where lenses suffer from the same issues as tweets. The issue of lenses is potentially a more tractable problem as we’d expect far fewer lenses than tweets. As a strawman, we could expect different localities to regulate lenses differently, with Twitter enforcing these geographical restrictions. In the next section, we also discuss the possibility of decentralized application servers.

Incentive design

While we presented proper incentive design as a goal, this proposal does not provide a solution to this question. Rather, the proposal is intentionally narrowly scoped so that we can test different incentive designs quickly with the market. Would an open platform and SDK be sufficient to incentivize developers to come? Certainly this enables researchers far more power to conduct data science on real users in production systems than before. Would government agencies value this problem enough to dedicate research grants to solving it? For companies, publishing a high-value lens provides an opportunity to promote content valuable to the company. For example, a Food Network lens could surface high-quality recipes as well as bias towards its own properties and media. Would that be enough incentive to build a lens, or would Twitter accept a revenue-share agreement to grow a food-Twitter network?

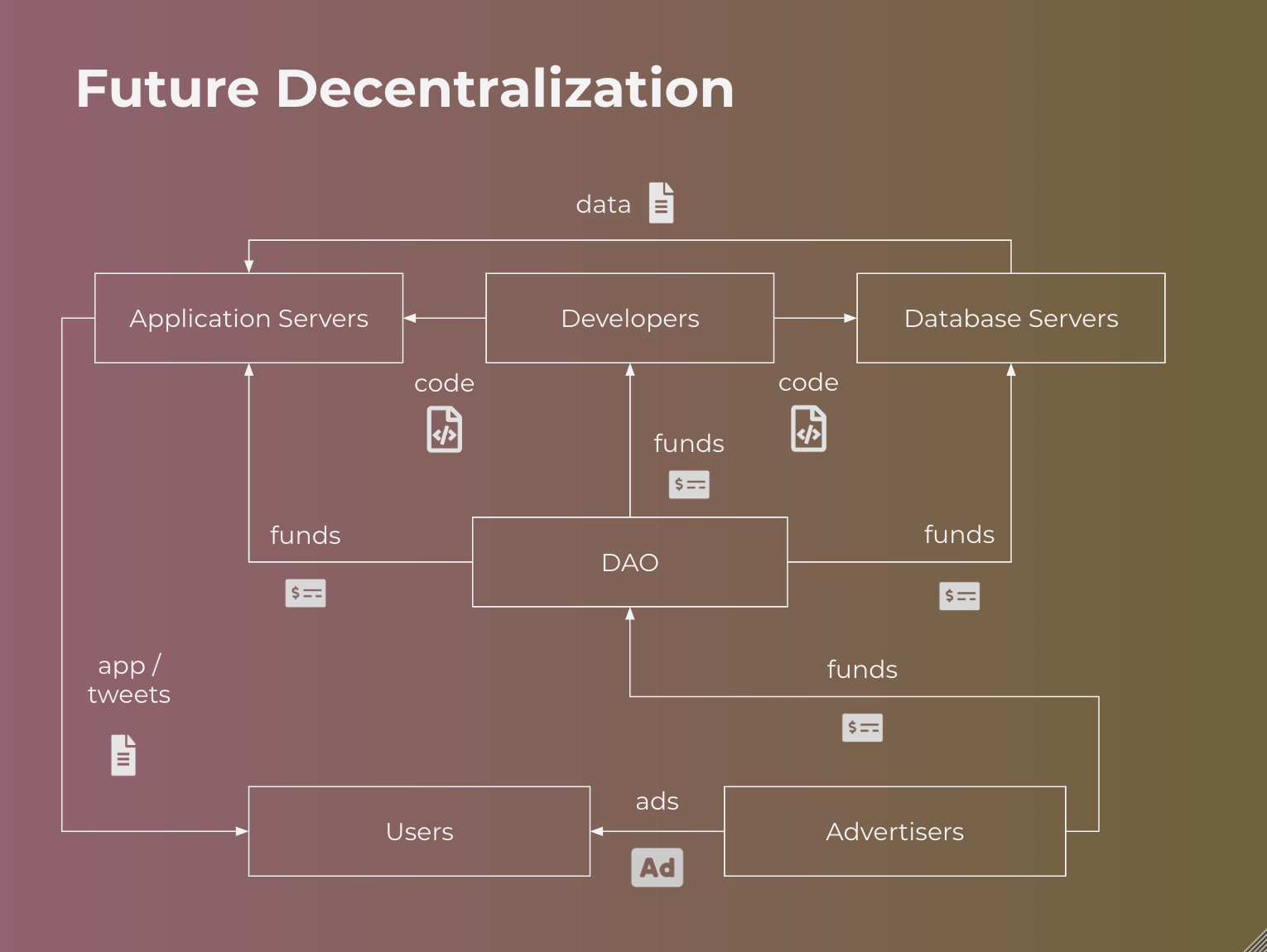

Future Decentralization

The proposal sketch above addresses many of the problems initially laid out in @jack’s tweets, with the caveat that it assumes Twitter will faithfully store and serve any data as required by the lens developer from its centralized infrastructure. This provides a path to enable fast experimentation of recommendation algorithms, but it does not fundamentally address the issue of data censorship by the platform. Fully decentralizing to combat censorship is a monumental engineering challenge that I would not recommend tackling as a first step. However, the proposal above lays the groundwork for evolving into a more decentralized platform if Twitter decides to in the future.

Let’s drastically simplify the problem and assume that the Twitter distributed system consists of clients, application servers, and database servers. I hold no illusions that their architecture is this simple, but the simplification makes it easier to explain how we’d decentralize and ancillary services could follow a similar path.

What Does It Mean to Decentralize a System?

There is a huge spectrum of how decentralization is defined. To many, it simply points to a feeling that we don’t want a single entity to have so much power, but what architectures constitute sufficient decentralization of power is an open question. I’ll propose a few suggestions:

- Permissionless participation: Anyone should be able to participate in the network and contribute to the system.

- Balanced participation: It is insufficient to be permissionless if a single party ends up dominating the network.

- Trustless: The Internet has changed. We cannot rely on assumptions of honest behavior in designing network protocols.

- Decentralized governance: Current platforms are ultimately controlled by profit-seeking shareholders. Users can only vote with their feet, which can be overly coarse to ask all users to take it or leave it. Because many of these businesses derive their strength from network effects, this puts users in a weak bargaining position. Decision-making processes should provide better ways to empower more stakeholders.

Verifiable computing provides a powerful primitive for constructing decentralized applications. By definition, these techniques ensure that remote parties compute correctly, even if they are malicious. This opens up the opportunity to allow anyone to join the system in a trustless fashion. However, verifiable computing is not a cure-all; it does not address poor performance, poor reliability, or data availability.

Decentralized application servers

Because application execution can be remotely verified, this opens up the possibility of allowing anyone to run an application server if the entire server-side application was ported to using verifiable computing primitives. As a strawman, cryptocurrency incentives can be tied to timely responses, which are paid out only when correctness has been verified. There remain a number of open questions on how to design a system that is sufficiently scalable, fast and reliable, but I believe the right building blocks do already exist.

Decentralized databases

Databases can similarly be remotely verified using verifiable computation. Using authenticated data structures, researchers have created optimized versions for SQL databases and blockchains. If we can remotely prove the correctness of query results, then anyone should be able to run a database of tweets. We can similarly provide cryptocurrency incentives for fast and reliable retrieval of data. If these databases represent disjoint sets, application servers can join results from multiple databases to compile a newsfeed view for a user.

Decentralized governance and cash management

We could apply a similar effort to run real-time advertising auctions trustlessly in application servers. Advertisers would pay into a wallet controlled by a smart contract or DAO, which will in turn pay network participants for work. The DAO, much like a corporation, can also continue to pay employees in employment smart contracts. We should be able to replicate Twitter Inc.’s (the company) entire self-sustaining business into a decentralized blockchain with real cash flows. It is not necessary to move Twitter to a token economic model that relies on a new token appreciating in value. Rather all of this can be built on top of an existing cryptocurrency, such as Bitcoin.

Thanks @jack!

I want to thank @jack for opening up this exciting possibility to engage with the open source and research communities to further improve Twitter. It’s a unique opportunity to solve one of society’s biggest challenges in a way that Twitter may find difficult to do alone. My hope is to simply bring to light an alternative way of thinking about the challenge that may yield a more incremental path for Twitter to follow. @jack and whoever you hire to lead this project, please don’t let this good intention die in vain.

To follow the conversation on Hacker News, check it out here